Searching for Mask Motivation: Completing the Behavior Design Equation

When cases of COVID-19 emerged in the U.S. and the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic, a shopping pandemonium ensued, clearing shelves and online providers of virtually all masks, gloves and other Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Of all the product shortages during this time, the PPE shortage was one of the most impactful shortages due to the increased need in hospitals and other frontline settings.

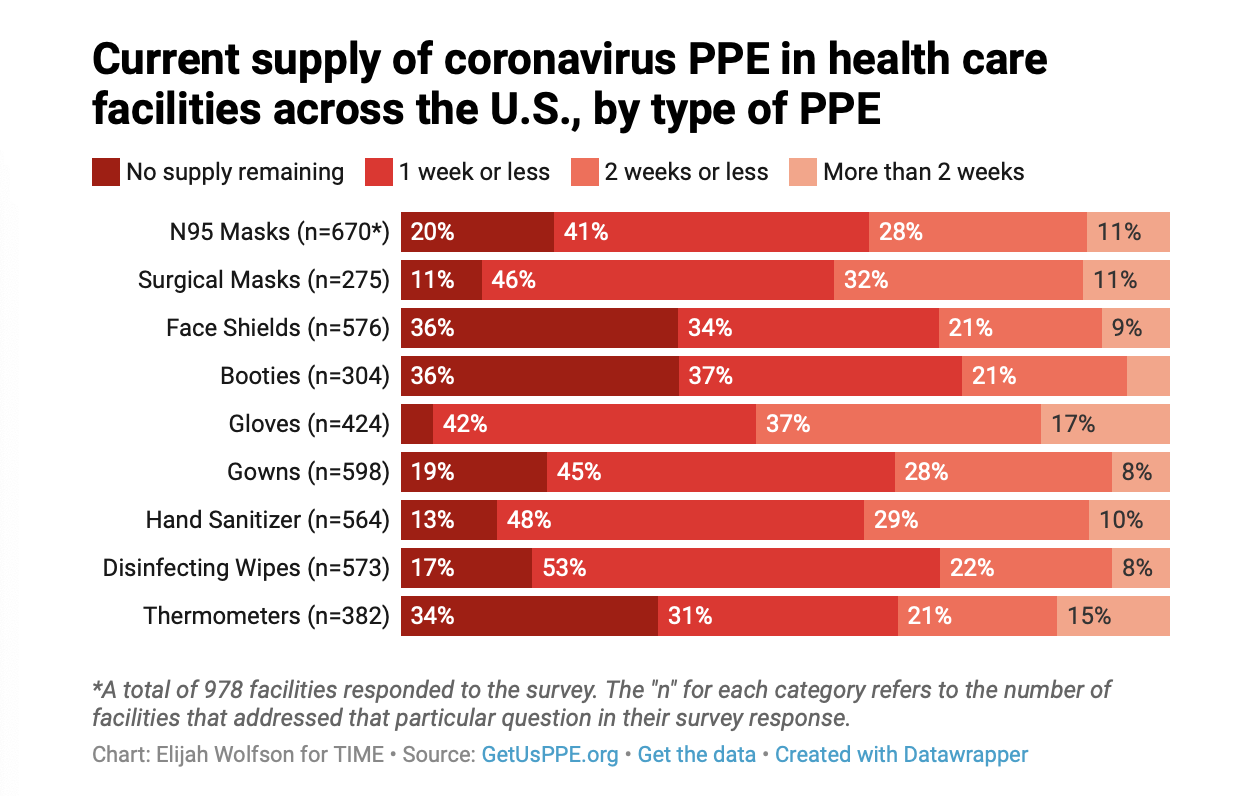

In some cases, health care workers had no choice but to reuse one mask for over three weeks. As shown in the chart below, a Time Magazine study from April 20th found that of the health care facilities that responded, approximately 90% of them did not have sufficient N-95 masks, surgical masks, or face shields to last longer than 2 weeks.

With the U.S. crossing 77,000 recorded cases per day, we’ve seen a strange turn of events where some Americans have been led to believe that facial coverings are no longer necessary. So how did people go from panic buying masks, groceries, and cleaning supplies to becoming so laissez faire about protecting the health and safety of themselves and others?

Since some areas have stabilized their cases and people have their hands on vital facial coverings, the attitude towards wearing them has changed. After analyzing the trajectory of best-practice measures - specifically wearing facial coverings - over the past few months and examining how U.S. culture and behavior has influenced the acceptance or rejection of best-practices we will propose how we can collectively use behavior and culture design to be better to each other and overcome this unprecedented time.

Trajectory of Mask Usage in the U.S.

In the beginning of the COVID-19 wave in the US, panic-buying led to a mass shortage of masks and other PPE - specifically surgical and N-95 masks. The country’s stockpile was not ample enough to meet the demands of hospitals and other frontline workers and states were competing against each other for supplies as reported on a seemingly endless loop. During this time, the public was advised against buying masks to counteract this shortage. Health organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advised that only sick individuals or individuals caring for sick individuals wear masks.

Despite the constant pleas of healthcare workers and government officials from the hardest hit states, the PPE shortage continued - but our fellow citizens began to step up. I’m sure you’ve heard the African proverb “it takes a village.” Well, our villages around the country kicked into high gear. Amateur seamstresses, small businesses, and large companies pivoted to mass produce masks for frontline workers, friends, family, and neighbors.

People sold masks, donated them, and experimented with different designs to make them comfortable, appealing, and accommodating for those with disabilities. Newspapers printed instructions for how to make your own mask. Youtube videos taught people how to sew masks. The images of people spending their days sewing for those in need were powerful. The shortage had given people a common goal to focus on during quarantine, and in lending a hand towards producing masks, people were answering our overarching research question, “How good can we be to each other?”

Then, something shifted. As the country began to open up in some areas, wearing a mask and staying at home became highly debated. Many businesses and stores reopened with the conditions that customers must wear facial coverings and maintain a safe social distance both indoors and outdoors. In fact, almost half of U.S. states have some sort of mask mandate in place, but many states such as Florida and Arizona which are seeing spikes in cases do not. While many Americans were elated at the thought of reopening following months of quarantine, the desire for “normalcy” for many Americans has made reopening more difficult and tumultuous. For example, in Flint, Michigan, one of the hardest hit states during COVID-19, a store security guard was shot and killed for denying a customer entry due to a lack of a facial covering.

Some less violent examples of American rejection of COVID-19 best practices include anti-lockdown protests and group gatherings lacking social distancing and facial coverings. A BBC article discussing this US backlash also depicts an image of groups of people sitting closely together and without facial coverings in Central Park. Another stark influencer of the mask-wearing divide is President Donald Trump, who did not wear a mask until a few months into the pandemic, while claiming that doing so is voluntary.

At protests against stay-at-home orders, social distancing and wearing facial coverings, some called facial covering mandates an infringement of their constitutional rights (fact check: it’s not). Others cried “my body, my choice” and “you are stifling our freedom”! In extreme cases, some Americans will go as far as to say that COVID-19 is not real, or that the effects of the pandemic are exaggerated and the government is just trying to control them. The emphasis Americans place on freedom and individual rights is extremely prevalent throughout U.S. history and culture, and has been manipulated as an argument against following best COVID-19 practices.

We see an emerging trend that shows that the more mandatory a task becomes in the U.S., the less people want to do it - especially when enforced by the government.

This trend is best explained by psychological reactance, which was proposed in 1966 by Jack Brehm. The theory of psychological reactance states that “individuals have certain freedoms with regard to their behavior. If these behavioral freedoms are reduced or threatened with reduction, the individual will be motivationally aroused to regain them”. The scale of one’s reactance will depend on how much importance they place on the freedom they feel they are losing and the perceived level of threat. This is one explanation for why we see some people protesting outside of state capitals with assault rifles, while others individually protest by trying to walk into a grocery store without a mask on.

Now that Masks are Abundant, How Do We Motivate People to Wear Them?

From studying BJ Fogg’s Behavior Model, we know that behavior happens when motivation, ability and prompt come together at the same time. The whole country has a prompt: preventing COVID-19 cases and deaths. Now that people have the ability to access masks and are encouraged to wear them, our country needs to (figuratively) come together and commit to wearing them with the same vigor it committed to creating them. How can we help our fellow Americans realize that the next step in taking better care of each other is to properly and consistently wear a mask when in public?

Although motivation can be variable, there are six factors that can increase motivation. They are seeking pleasure, avoiding pain, seeking hope, avoiding fear, seeking acceptance, and avoiding rejection. With these in mind, I read Dr. Jill McDevitt’s viral post about how to get people to comply with wearing face masks. Dr. McDevitt is a sexologist and proposed advice based on four decades of research on promoting condom usage. Her advice reiterates that you want to normalize mask wearing, which will make people seek acceptance and avoid rejection, but you want to be careful not to shame, guilt, or judge people into compliance. It is especially interesting that in her experience, using fear is not a great tactic, which means that the avoiding fear factor may not be the best factor to focus on when establishing messaging around face covering compliance. Instead, she encourages positive peace by preaching to be honest about the risks of transmission, which directly relates to the avoiding pain factor and allows some to seek hope that by taking this simple action, they can help reduce the viral transmission.

Another interesting tactic in Pennsylvania is that the state has taken the demands for freedom from mask wearing and instead, used the concept of freedom to promote face masks. Their messages and graphic designs promote masks as a means to achieve more freedom as when people wear masks, cases decrease, and the state will be allowed to reopen. Here the state is actively trying to combat psychological reactance by showing citizens that their freedom is not being taken away, rather they are showing them the path back to “normal”.

Moving Forward

Though we are all itching for some sort of normalcy, it is imperative that we take the proper steps to ensure the health and safety of all. We must work to combat politicization and the psychological reactance displayed throughout the country. We must bring the focus back to the fact that wearing masks has proven to be effective in slowing the spread of COVID-19 compared to not wearing masks.

As individuals, in order to take better care of each other we must commit to wearing facial coverings in public where required by our government. We need to wear them properly, which means ensuring it securely covers our mouth, nose, and chin. Simply put, wear a facial covering to be good to each other. Shouldn’t that be motivation enough?

To learn more about the impact of COVID-19 on various aspects of our society, head over to our PeaceX Global Response Initiative research findings

Written by: Abigail Gard and Elisa Selamaj